What Comes When the Global Carbon Budget Is Gone? The CRO and a Negative Carbon Economy

At our present GHG emissions level, it is clear that emission reductions alone will not limit global surface temperature increase to the Paris Agreement's 1.5°C by end of century. Justin Macinante, PhD, MEL, LLB, a Climate Change Research Fellow at the University of Edinburgh Law School, presents a proposed mechanism that could drive the necessary CO2 removals — and meet the Paris target.

Global carbon budget

At the present level of GHG emissions, it is clear that emission reductions alone will be insufficient to achieve the Paris Agreement aspirational target of restricting average global surface temperature increase to 1.5°C by the end of the century. As well, emission reductions alone will be insufficient to meet the various commitments of signatory governments, often framed as achieving ‘net zero’ by a specified date.

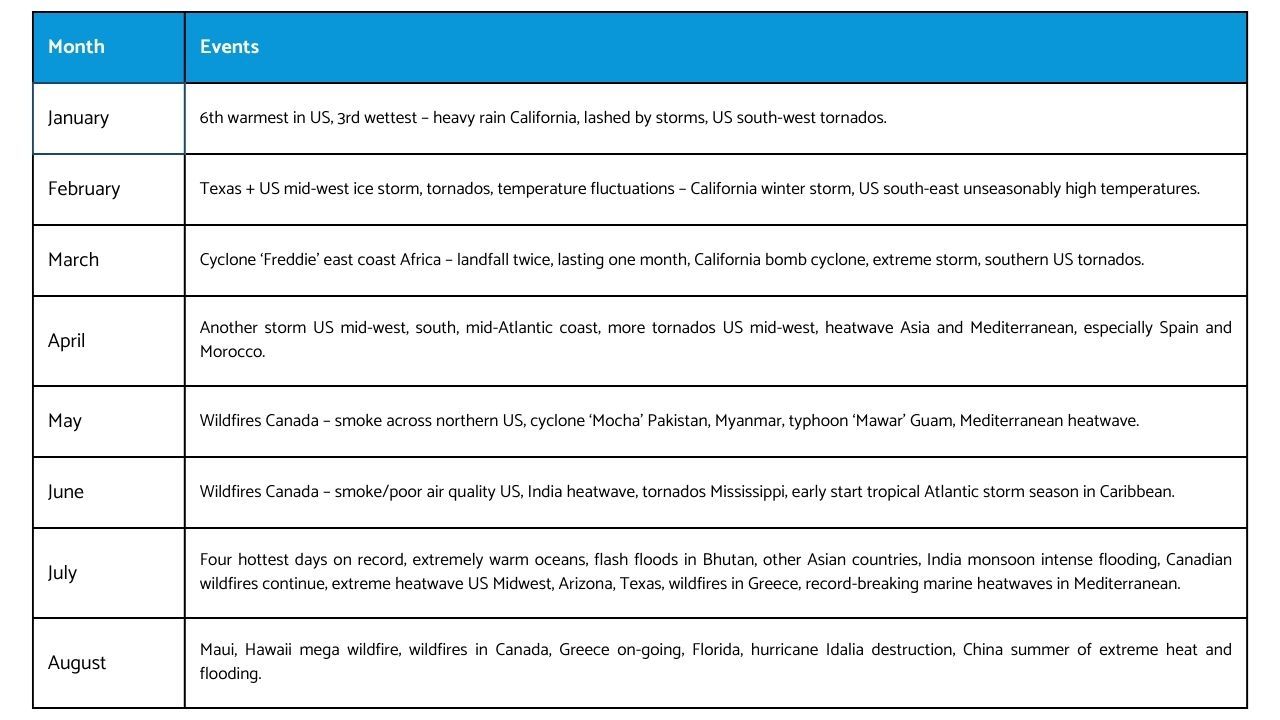

The UN World Meteorological Organization gives a 66% likelihood that the global average surface temperature will exceed the long-term average, at least temporarily, by 1.5°C in the next 5 years. Researchers predict the global carbon emissions budget for staying under 1.5°C to be exceeded within the next decade. Emissions need to be significantly reduced and warnings continue to be given of this need: the carbon budget for staying below a 1.5°C increase will soon be exhausted. The Earth’s geophysical systems seem to be issuing warnings as well: extreme weather records are piling up in 2023, with July being the hottest month on record.

Once we exhaust the global carbon emissions budget to remain under 1.5°C — in other words, 'overshoot' — we are in ‘carbon budget deficit’ territory. In which case, every additional tonne of carbon emissions will increase this carbon debt that must be extinguished if we are to have any hope of achieving the 1.5°C target by the end of the century.

Removals, a necessity

The need for removals of carbon from the atmosphere has long been recognised by the IPCC. Land-based removals include biological means — such as afforestation and reforestation, geological means — such as direct air capture and carbon storage (DACCS) and bioenergy with carbon capture and storage (BECCS), and lithospheric means— such as biochar and enhanced rock weathering. Although these solutions need to rapidly grow to an industrial scale comparable to the energy sector to achieve the impact necessary, this is a virtually non-existent industry sector at present. And there are ocean-based removals, including chemical approaches, such as increasing alkalinity, and biotic approaches, such as promoting photosynthesising organisms like seaweed or adding nutrients to promote phytoplankton growth. All these approaches need to be massively scaled up as a matter of urgency. To drive the scaling up of removals requires a mechanism to significantly increase investment, that is, a mechanism that will significantly increase the incentives to invest in removals.

Once the carbon emissions budget is exhausted, emissions trading schemes based on trading emission allowances cease to be logical. By definition, there are no ‘allowable emissions’ left: emissions after that point only increase the budget deficit, that is, the carbon debt.

Calling a spade, a spade: emissions as carbon debt

Climate change researchers have proposed a mechanism to address this situation: once there is overshoot, emissions would be defined legally as carbon debt that needs to be repaid — just as is the case for other debt obligations. And to the extent that the ‘debt facility’ is extended to the emitting entity, as debtor, that entity would need to pay interest on it.

How could this arrangement work? Johannes Bednar, PhD and colleagues at the International Institute of Applied Systems Analysis in Vienna and Oxford University provide the argument for such a mechanism – the Carbon Removal Obligation (CRO). Recently, I have been working with them on how such a proposal could be implemented (Bednar, J., et al., “Beyond Emission Trading to a Negative Carbon Economy, The Carbon Removal Obligation and its Implementation”, 2023; submitted for publication).

The CRO policy framework, consists of two elements: a principal mechanism obliging emitters of a tonne of CO2 to remove a tonne of CO2 at the time of maturity of the CRO — issued to them as a legal instrument. This is the ‘capital’ borrowed and that needs to be repaid. Additionally, CRO holders would pay a fee: the ‘interest’ on the capital borrowed. This element of the mechanism is used by regulators to steer the carbon emissions and removals pathways.

Role for central banks and commercial banks

Who would be the regulators in such an arrangement? In the legal framework proposed, control of the climate change mitigation pricing lever — that is, the interest element — is placed in the hands of the traditional managers of financial stability, namely central banks. Doing so allows the externality of carbon emissions and climate change mitigation response management to be integrated into the economic mainstream.

Commercial banks would issue CROs, on which they charge interest, to their emitting customers in much the same way they provide debt finance to customers. Similarly, the central bank would require commercial banks to maintain reserve accounts with it, on which it would charge a base rate of interest. Thus, implementation of the proposed framework applies legal mechanisms that would be familiar to all entities involved.

Carbon debt as evidenced by the CRO instruments would be extinguished by the emitter entities acquiring and retiring removal units, which are generated and issued by removal projects. Hence, the need to extinguish carbon debt would drive demand for removals, prompting greater investment in removals projects.

Interest payments on the commercial banks’ accounts with the central bank – and perhaps also a portion of the interest payments by the emitter entities to their issuer commercial banks — could be applied to a fund, like a sovereign fund, against future climate change management risks.

In this way, applying the polluter pays principle to make emitting entities responsible for removing their emissions also addresses intergenerational equity, by providing for the cost of achieving the 1.5°C target by the end of the century. It leverages existing legal mechanisms to ensure that the removals will be real.

Standard

Additionally, it is proposed that a standard be established for the creation of removal units by removals projects, including in relation to ecosystem and social impact benefits. This would also facilitate a smoother running, more efficient market by reducing transaction costs and enhancing price discovery. At the same time, this would increase the potential for cross-jurisdictional application and trading.

Early action by governments to promote development of such a standard and put in place legislative measures indicating the direction of policy, such as a timetable for introducing CROs, would enhance private sector confidence and engagement in developing and scaling up the removals project sector.

Conclusion

The CRO policy framework sets out mechanisms by which substantially more ambitious emissions mitigation and significantly greater deployment of CO2 removals might be achieved. It is innovative in placing the climate change mitigation pricing lever in the hands of the traditional managers of financial and price stability, namely central banks, integrating the climate change mitigation response management into the economic mainstream, as part of core economic and financial management. It can drive the negative carbon economy necessary to limiting average global surface temperature increase to 1.5°C by the end of the century — notwithstanding the impending overshoot soon to be upon us.

Selected 2023 extreme weather-related events

About the Author:

Justin Macinante, PhD, MEL, LLB

Research Fellow in Climate Change, University of Edinburgh Law School

Research Associate, CO2RE

PHOTO: Cody Chan | British Columbia Forest | Unsplash

Read perspectives from the ISSP blog